Voltaire Days

Deadline for applications: 20 February 2018

Organizer: Guillaume Métayer (CELLF – CNRS)

Partners: CELLF (UMR 8599), Société des Études Voltairiennes, CEFRES, CERCLL (Jules Verne University, Picardie)

When & where: 22-23 June 2018, Paris-Sorbonne University

Language: French and English

Contact: gme.metayer@gmail.com

Outline

No-one among the Enlightened French writers and philosophers entertained such extensive relations with the German-speaking world as Voltaire. Besides his many stays in Germany, and his well-known appointment as chamberlain to Frederick II at the Prussian court, Voltaire stayed in Gotha and Aix-la-Chapelle. His visits, relationships and above all his readings sparked many works of various genres, most famously, but not only, Candide (1759). Westphalia was also the philosophical and imaginative inspiration for an important chapter of L’Essai sur les Mœurs (“Essay on Universal History, the Manners, and Spirit of Nations”, 1756) and Voltaire wrote another, more detailed historical account, at the request of the Princess of Saxe-Gotha, entitled Les Annales de l’Empire (“Annals of the Empire”, 1753). L’Histoire de la guerre de 1741 (merged and adapted within the Précis du Siècle de Louis XV, “Short history of the Age of Louis XV“) also takes account of this political and cultural unity with its changing borders. As a historian, Voltaire addressed crucial topics such as the struggle between temporal and spiritual powers, in particular between papacy and the Holy Empire; the Reformation; or more widely, Europe’s political and religious identity.

Yet, Voltaire’s intense interest for Germany is pervaded with ambiguity: he is interested in the Empire’s policy, history and contemporary hope for a forthcoming “philosopher king” in Berlin at the expense of German literature, language and arts, which he looked down on and readily derided. This inconsistency explains the complex and polemical nature of Voltaire’s reception in the German-speaking world. Supporters and epigones prevailed to begin with but were soon taken over, with a few exceptions (Schiller, Goethe, Heine), by the critiques of the representatives of the literary and philosophical German renewal. Even before Romanticism, Lessing set the tone for this harsh critical tradition, continued by August Wilhelm Schlegel. Only from the 1870s, with the re-evaluation of David Friedrich Strauss, Dubois-Reymond, and most of all Nietzsche, did the figure of Voltaire evolve into becoming a cornerstone of the European Enlightenment.

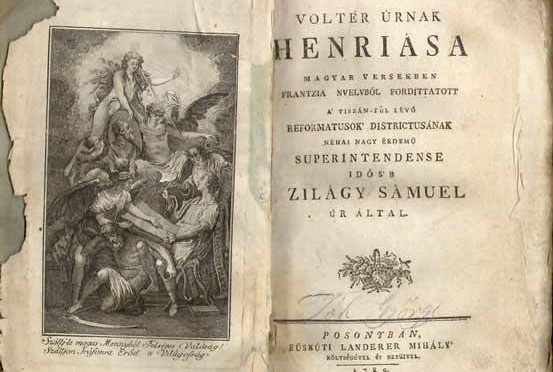

Such interaction in time between Voltaire’s German world-view and the German, and more largely Central European reception of the philosopher writer will be at the core of this conference, being held forty years after the Mannheim conference*. Papers dealing with reception, circulation, and translation studies, or seminal monographies—insofar as they attempt to deal with both dimensions of this hermeneutic Wechselwirkung—will be welcome. The fate of Voltaire’s thought in the Austrian hereditary possessions (Hungary, Galicia) would also offer very interesting case studies.

* Voltaire und Deutschland. Quellen und Untersuchungen zur Rezeption der Französischen Aufklärung. Internationales Kolloquium der Universität Mannheim zum 200. Todestag Voltaires [Mannheim, 1978], Stuttgart 1979.