VIe séance du Séminaire du CEFRES 2021-2022

Biopolitique, espace et savoirs bureaucratiques au XXe siècle : perspectives centre-européennes

Date : mercredi 8 décembre 2021 à 16 h 30

Lieu : au CEFRES et en ligne (pour vous inscrire, écrivez à l’adresse : claire(@)cefres.cz)

Langue : anglais

Avec :

Nikola Ludlová et Vojtěch Pojar, doctorants à l’Université d’Europe centrale et au CEFRES

Notre séance consiste en deux présentations sur la biopolitique en Europe centrale et orientale. Nous nous concentrons sur les savoirs scientifiques et le rôle des experts et des bureaucrates pour leur production et leur circulation. Nos présentations peuvent sembler disparates en apparence, puisqu’elles se focalisent sur deux disciplines scientifiques différentes – la démographie et l’eugénique – et sur deux époques distinctes du XXe siècle. Néanmoins, nos présentations reposent sur trois hypothèses formulées par l’histoire des sciences que nous souhaitons rappeler.

Premièrement, nous pensons qu’il n’existe pas de savoir scientifique qui « flotterait » sans attache et en toute autonomie et considérons au contraire que le paradigme spatial nous offre des outils pour une analyse plus convaincante. Nous explorons donc le savoir scientifique dans son mouvement et étudions sa circulation à travers divers contextes géographiques et institutionnels.

Nous nous efforçons ensuite de remonter, à partir des savoirs scientifiques, jusqu’aux pratiques qui les ont produits. En particulier, nous avons tous les deux réalisé au cours de nos recherches que les bureaucraties jouaient un rôle majeur, et jusqu’ici sous-estimé, dans la production et la circulation des connaissances biopolitiques. Avec Theodore Porter, nous considérons ainsi que les études du savoir bureaucratique montrent que les sciences du social sont « plus ou moins continues avec les formes d’expertise développées dans l’appareil étatique ainsi que dans les organisations responsables des réformes faisant intervenir le clergé, les juristes et les médecins ainsi que les scientifiques ».

Nous pensons enfin qu’établir un lien entre savoirs scientifiques et pratiques bureaucratiques nous aide à repenser les rôles de la biopolitique et de la bureaucratie en Europe centrale et orientale. Cependant, ce cadre régional apporte également des défis analytiques qui sont principalement liés à la notion de dis/continuité. Les récits historiques conventionnels représentent l’histoire des États, telle la Tchécoslovaquie, comme une série de ruptures radicales liées à la succession des différents régimes politiques. Toutefois, nos présentations montreront que prendre pour objet les connaissances scientifiques, y compris celles qui façonnent la biopolitique, permet de révéler une histoire à la fois plus complexe et plus inquiétante.

Résumé des deux interventions

Indvidual and Collective Identification and Evidence of Roma in Twentieth Century

par Nikola Ludlová

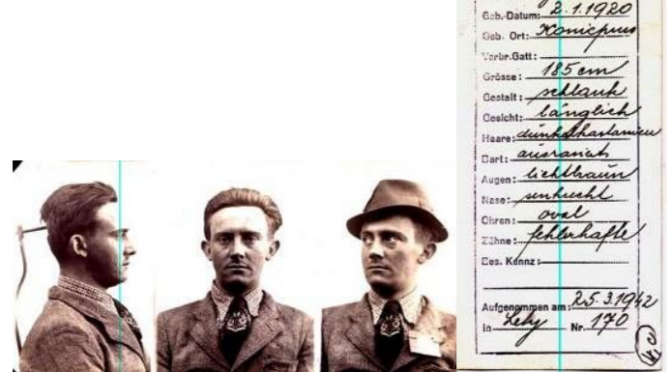

Demography and its close associate statistics belong among the major intellectual and institutional offshoots of the modern European bureaucratic state whose further development continued to be tightly linked with state governance. The chapter focuses on ethnic statistics and evidence targeting Roma as cases of knowledge making most directly linked with state surveillance and management of Romani population. Population censuses and demographic surveys conducted by demographers, the ‘gypsy’ registers conducted by criminal bureaus and evidence pursued by national councils in the framework of social work generated data which circulated among these scientific and administrative institutional agents. Administrative bodies drew on primary demographic statistics and demographers used administrative data mostly as sources of secondary data, but also for comparative purposes, especially as concerns the data on the size of the Romani population. On account of the credence and authority attributed to these scientific and administrative ‘paper’ technologies, the politically constructed representation of Roma, presented as objective reflection of reality, had tangible mostly negative consequence for people subsumed under this category. Identification and evidence were indispensable to the realization of the racial policies of the Nazi Germany and analogically, the ability and sources to achieve erasure from the evidence and disguise one’s identity could save lives. Spanning the period of almost entire twentieth century, I trace dis/continuities in practices of identification, categorizations and evidence of the targeted objects across these specialized bureaucratic and scientific realms and embed the history of registration and personal identification practices by civil and security bureaucratic agents and by scientific experts, i.e. demographers, in a longer history of population identification and registration as instruments of governmentality indispensable to the projects of state and nation-building since the 19th century.

Eugenics in Post-imperial Transitions: Concepts, Spaces and Practices

Vojtěch Pojar

My talk explores some consequences of the imperial turn in Habsburg studies for the history of eugenics in East Central Europe. To fully seize these opportunities, I argue, we need to move beyond the categories derived from the classical history of ideas. History of knowledge offers us more useful tools in this regard. I will spell out how a focus on concepts and their circulation, on spaces, and on practices may help bring empire into the history of eugenics in East Central Europe, and vice versa.

First, an analysis of concepts used by eugenicists in early twentieth century Austria-Hungary reveals how various actors drew on eugenics to think through their imperial situation, sometimes in startling ways. Moreover, conceptual history makes it possible to trace the continuities and reframing of such eugenic knowledge after the collapse of the empire and the emergence of its successor states. Second, I argue that a focus on the spaces in which these concepts circulated not only shows the transnational nature of eugenic knowledge, but also illuminates how it operated on multiple scales, local and global, national and imperial. Third, an analysis of practices and institutions in which eugenic knowledge was embedded opens up new possibilities for explaining its changes. How can we explain the rise of radical biopolitics in interwar post-Habsburg Central Europe remains the crucial question here. However, my talk will suggest how the perspective of imperial history and history of knowledge can help us answer this question in a more complex way.

Suggested Readings (for both presentations)

- Maria E. Kronfeldner, ‘“If There Is Nothing beyond the Organic…”: Heredity and Culture at the Boundaries of Anthropology in the Work of Alfred L. Kroeber’, NTM Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Wissenschaften, Technik und Medizin 17, no. 2 (May 2009): 107–33.

- Maurizio Meloni, ‘A Political Quadrant’, in Political Biology: Science and Social Values in Human Heredity from Eugenics to Epigenetics (Basingstoke; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 93–135.

- Theodore M. Porter, ‘Revenge of the Humdrum: Bureaucracy as Profession and as a Site of Science’, Journal for the History of Knowledge 1, no. 1 (17 December 2020): 1–5.