Příběhy o ženství v modernismu střední a východní Evropy (1870–1970)

Organizační rada: Naïma Berkane, Mateusz Chmurski, Cécile Rousselet a Clara Royer

Kdy: 4.-5. června 2026

Kde: Paříž

Pokyny pro podání přihlášek: Vaše návrhy (ve francouzštině nebo angličtině) ve formě názvu, shrnutí o délce přibližně 300 slov a biograficko-bibliografické poznámky zašlete do 1. prosince 2025 na adresu: femininenarratives@gmail.com

Vědecká rada: Biljana Andonovska, Arnaud Bikard, Mateusz Chmurski, Alessandro Gallichio, Petra James, Luba Jurgenson, Jean-François Laplénie, Jasmina Lukić, Lena Magnone, Jelena Petrović, Alexandra Wojda

Feminine elements have been investigated as narratological concepts, as conceived of by feminist narratology (Prince, [1987] 2003; Page, 2006; Lanser, 2010, among others). As Susan S. Lander states, “the field of gender and narrative stakes its diverse approaches on the shared belief that sex, gender, and sexuality are significant not only to textual interpretation and reader reception but to textual poetics itself and thus to the shapes, structures, representational practices, and communicative contexts of narrative texts” (2013, § 3). At the margins of narrative constructions, feminine figures and motives have evoked imaginaries of deviation (eroticization, exoticization, racialization, etc.). When leading, these figures represent one of the arenas—or rather, bodies—through which the arts and artists have negotiated their relationship to the narrative.

This conference is the fourth of a cycle dedicated to “Women and Clash(es) of Emancipation” organized by Eur’ORBEM (Paris) and CEFRES (Prague). It aims to tackle the narratological consequences induced by feminine figures and motifs in modernisms. The previous works have contributed to the writing of women’s history: questioning canons and their formation, they offer tools to reread the texts and reevaluate their reception. Our goal is to probe the aesthetic specificities of womanhood narratives, thus analyzing the role of the feminine in the creation and development of narratives, insofar as they establish specific relationships with them.

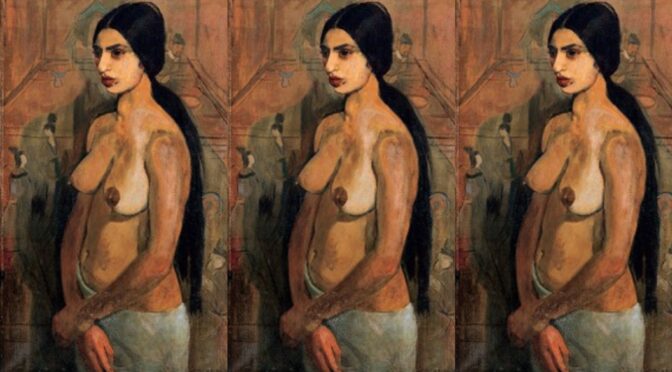

“Narrative womanhood” will be investigated from a transmedial perspective. Following Jean-Marie Schaeffer’s study of narrative processes, our enquiry seeks to encompass literature and images, whether still or in motion. This narrative turn highlights that while the “co-presences” and “spatial contiguities” of still images cannot produce an “event sequence,” they still “narrativize” and “temporalize” (Schaeffer, 2020). Consequently, we include all mediums that develop narrativity through their own temporal and/or spatial means, or their “demonstrative” or “representational” potentials. We will therefore examine, through this lens, media as diverse as the visual arts, dance, literature, performing arts, theater, erotic novels, and pornographic images (see Preciado, 2011), but this list is by no means exhaustive.

Modernisms—broadly defined to encompass their forerunners and their direct successors, hence our choice of the period 1870-1970—seems to be a privileged angle from which reflecting on both the narrative capacities of various media (for instance, reduction in painting may reject narrativization alongside representation: Ilg, 2002) and on the aesthetic capacities of the manifestations of womanhood. In this respect, the Balkans, Central and Eastern Europe provide a particularly rich field for this study, given the vitality of the modernisms that emerged there in the late 19th century, leading to a series of displacements and crises in the 20th century (Chmurski, 2018), particularly in the relationship between the arts, narration, and representation. These phenomena were closely tied to the roles assigned to womanhood.

Indeed, since Walter Benjamin, modernities have been approached as periods of crisis, intimately linked to questions of identity, particularly in the region under study (see Le Rider, 1990). These crises are above all crises of representation of modernity, which modernists have tended to ascribe to the feminine on a narrative level for various reasons—which shall be explored—that stemmed from the imaginaries associated with womanhood and from socio-cultural evolutions and emancipatory dynamics facilitated by modernity.

Therefore, several phenomena need to be examined together. Womanhood placed in a crisis—through various forms of violence perpetrated against women, their invisibilization, disfigurement, relegation to radical otherness, etc.—should be considered as a crisis, mirroring those of aesthetic modernities. Narrative womanhood can thus be seen as a scene where discursive, narratological, and aesthetic questions are negotiated. The narrative, its foundations, and its reflexivity must be taken into account in the same movement. In this way, the feminine becomes as much a narrative element as it is narrativized, as much representative as it is aesthetic.

Obviously, these gendered considerations must be approached with subtlety. Modernisms from the Balkans, Central and Eastern Europe saw many women artists emerge (Magnone, 2024). How did these female voices respond to narrative and representational issues? What variations did they develop that could rise to new emancipatory or even counter-emancipatory dynamics for women? Did they reject these modernist codes or, on the contrary, did they appropriate them, in which case the hypothesis of their desemantization could be confirmed? Therefore, the various strategies employed, whether they involve divergence, recuperation, subversion or opposition, should cast a light as much on the relationship between women artists and their medium and the aesthetics produced by modernisms as on the resistance or adherence of these women authors and artists to the historical, political, or social phenomena reflected in these representations.

*

This study of womanhood in relation to the crises of modernisms will therefore allow us to reevaluate female presences, no longer solely through what they tell us about their status in the narrative, but mainly as a material through which the arts work their way out of the narrative and thereby shape artistic forms.

Several questions may be explored:

- Can we approach the spectacle of and on womanhood, and thereby the pleasure it provides to readers/viewers (Mulvey, 1975) as a place for renegotiating narrative regimes and for a new configuration in the distribution of the sensible (Rancière, 2000)? Thus, questions of reception, gaze, and visual culture, central to feminist studies, could be reconsidered in light of these aesthetic perspectives.

- Whether the feminine appears as an object supporting formal innovation or as a subject inspiring it, could this lead us to think afresh about the notions of creator and creature in the arts? Does female creation, through its enunciative agency, modify or even abolish this framework, and produce new forms? How does the emphasis on intimate narratives and bodies, particularly in performance art, contribute to blurring the boundaries between creator and creature? Does it go so far as to transform the very notion of authorship (Petrović, 2019) and authority over creation (Tumbas, 2022)? Also, how do female performers conform to or resist this role assigned to them? Can their presence in the artwork disrupt the ways womanhood is displayed?

- In what ways do women contribute to the plot? What role do they play in the narrative dynamics? Here, we can refer to Paul Larivaille’s or Jean-Michel Adam’s work on the importance of “trigger elements” in plot development (Larivaille, 1974; Adam, 1992). The structuralist and semiotic approach will enable us to examine the roles that female characters play in narratives, oscillating between power and powerlessness. However, it will obviously also be necessary to go beyond these initial observations, and to grasp female characters through a multiplicity of complementary approaches. Which needs renewed methodological tools. Indeed, if the female figure is a sign (in the sense used by Philippe Hamon, for example), it is by virtue of numerous characteristics that need to be explored jointly.

- Do womanhood narratives contribute to creating something unheard of in narrative and generic systems, in the manner of what Stanley Cavell calls the “creation of the new woman”, and conversely, “the new creation of woman” (see also on film genres: Dumas, 2021, Jovanović, 2014)? Is this idea only effective in cinema? How can we conceive of such dynamics in the genres of visual arts, theater, dance, architecture, etc.? How do they contribute, in these different artistic fields, to blurring the porous boundaries between figuration and narration? How can the feminine play a role in “narrative figurations” (beyond questions of narrative figuration in the visual arts)?

- Comparative approaches will also be valued insofar as they question the place of these feminine elements according to narrative mediums. If we consider the feminine as critical dynamics within narratives, to what extent can we consider specific crises, or different ways of questioning these crises, according to the narrative arts? These questions may also lead us to reflect on transmediality, studying works that involve dynamics of hybridity and intersemioticity—what, for example, of works that integrate multiple temporalities through these processes? sequential forms? single images with multiple scenes? —and the very framework of the constitution of a corpus and of comparative research. How do these dynamics of constructing a transmedial object of study promote and encourage redefinitions of the feminine as a generator of innovative narrative dynamics?

Hlavní řečnice: Nebojša Jovanović

Na základě tohoto sympozia vznikne publikace.

Indicative bibliography

ACHARD, Pierre, « Formation discursive, dialogisme et sociologie », Langages, vol. 29, n°117, 1995, p. 82‐95.

ADAM, Jean-Michel, « Le prototype de la séquence narrative », in Les textes : types et prototypes. Récit, description, argumentation, explication et dialogue, Paris, Nathan, 1992, p. 45‐74.

ARAMBASIN, Nella, « Femmes mythiques : une enquête biographique entre histoire et fictio », in Philippe Baron, Dennis Michael Wood et Wendy Perkins (dir.), Femmes et littérature, actes du colloque international (Universités de Birmingham et de Besançon, 16 et 17 janvier 1998), Besançon, Presses universitaires Franc-Comtoises, 2003, p. 51‐68.

BARTHES, Roland, Le plaisir du texte, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 1973.

BESSIÈRE, Jean, « Introduction », in Jean Bessière (dir.), Figures féminines et roman, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1982, p. 5‐9.

BRIDENTHAL, Renate, KOONZ, Claudia, STUARD, Susan Mosher (dir.), Becoming visible: women in European history, Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1977.

BROWNSTEIN, Rachel M., Becoming a heroine: reading about women in novels, New- York, Columbia University Press, 1994.

CAMPBELL, Joseph, Goddesses: Mysteries of the Feminine Divine, Novato, New World Library, 2013.

CAVELL, Stanley, Pursuit of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage, Harvard, Harvard Film Studies, 1984.

CHMURSKI, Mateusz, Journal, fiction, identité(s), Paris, Eur’Orbem Éditions, 2018.

DAVIS, Natalie Zemon, Women on the Margins: Three Seventeenth-century Lives, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1995.

DE BAECQUE, Antoine, La cinéphilie. Invention d’un regard, histoire d’une culture. 1944-1968, Paris, Fayard, 2013.

DEUTSCHMANN, Peter, « Les rôles-types féminins dans les pièces de théâtre tchèque de převrat », in Jean Boutan et Cécile Rousselet (dir.), Soldates inconnues. Militantes de l’arrière. Figures de femmes aux confins de l’Europe en guerre, Paris, L’Improviste, 2022

DUBY, Georges, PERROT, Michelle (dir.), Histoire des femmes en Occident, 5 vol., Paris, Perrin, 2002 [1990-1992].

DUCROT, Oswald, Le Dire et le Dit, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1985. GENETTE, Gérard, Discours du récit [1972], Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 2007.

DUMAS, Louise, Automobile et cinema : un long métrage, Berlin, Peter Lang, 2021.

ERIKSEN, Anne, « Être ou agir ou le dilemme de l’héroïne », in Pierre Centlivres, Daniel Fabre et Françoise Zonabend (dir.), La fabrique des héros, Paris, Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, coll. « Ethnologie de la France », 2015, p. 149‐164.

FIX, Florence, PLANA, Muriel (dir.), Présences et représentations des corps des femmes dans la littérature et les arts, Dijon, Presses universitaires de Dijon, 2023.

GREIMAS, Algirdas Julien, Sémantique structurale. Recherche de méthode, Paris, Larousse, 1966.

GUILLEMIN, Océane, D’Hélène à Lilith : Figures de femmes étrangères en Suisse romande (1890-1914), Lausanne, Archipel, 2018.

HAMON, Philippe, « Pour un statut sémiologique du personnage », Littérature, vol. 6, n°2, 1972, p. 86‐110.

ILG, Ulrike, « Painted Theory of Art: «‘Le suicidé’ (1877) by Edouard Manet and the Disappearance of Narration », Artibus et Historiae, vol. 23, n° 45, 2002.

JOVANOVIĆ, Nebojša, Gender and Sexuality in the Classical Yugoslav Cinema, 1947-1962, Thèse de doctorat, Budapest, Central European University, 2014.

KADISH, Doris Y., Politicizing Gender: Narrative Strategies in the Aftermath of the French Revolution, New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 1991.

KERMODE, Frank, The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction, Oxford, New York, Oxford University Press, 2000 [1967].

KRUTIKOV, Mihail, Yiddish Fiction and the Crisis of Modernity, 1905-1914, Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2001.

LANSER, Susan S, « Are We There Yet? The Intersectional Future of Feminist Narratology », Foreign Literature Studies, vol. 32, 2010, p. 32-41.

LANSER, Susan S., « Gender and Narrative », the living handbook of narratology, en ligne, 2013, § 3. URL : https://www-archiv.fdm.uni-hamburg.de/lhn/node/86.html#Prince

LARIVAILLE, Paul, « L’analyse (morpho)logique du récit », Poétique, n°19, 1974, p. 368‐388.

MAGNONE, Lena, « Mothers of the nation, or how national women writers are created », Gender and Nation in East Central Europe, CIESLAK, Marta, MULLER, Anna, (ed.s), Bloomsbury, 2024.

MAINGUENEAU, Dominique, Le Contexte de l’œuvre littéraire. Énonciation, écrivain, société, Paris, Dunod, 1993 ; « Paratopie », Glossaire. Disponible en ligne : http://dominique.maingueneau.pagesperso-orange.fr/glossaire.html.

MILLER, Meredith, Feminine Subject in Masculine Fiction. Modernity, Will and Desire, 1870-1910, Londres, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

MINTURN, Kent, « Greenberg Misreading Dubuffet », Abstract Expressionism: the international context, New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 2007.

MULVEY, Laura, « Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema », Screen, vol. 16, n°3, 1975, p. 6-18.

PAGE, Ruth E., Literary and Linguistic Approaches to Feminist Narratology, Basingstoke, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

PAILER, Gaby, BÖHN, Andreas, SCHECK, Ulrich et al., Gender and Laughter: Comic Affirmation and Subversion in Traditional and Modern Media, Amsterdam, New York, Rodopi, 2009.

PERROT, Raymond, De la narrativité en peinture : Essai sur la Figuration Narrative et sur la figuration en générale, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2005.

PETROVIĆ, Jelena, Women’s Authorship in Interwar Yugoslavia: The Politics of Love and Struggle, Londres, Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

POLLOCK, Griselda, Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art Histories, Londres, Routledge, 1999.

PRECIADO, Beatriz, Pornotopie : Playboy et l’invention de la sexualité multimédia, Paris, Climats, 2011.

PRINCE, Gerald, A Dictionary of Narratology, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, [1987] 2003.

PROPP, Vladimir Âkovlevič, Morfologiâ skazki, Leningrad, Academia, 1928. / PROPP, Vladimir, Morphologie du conte, trad. Marguerite Derrida, Tzvetan Todorov et Claude Kahn, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 1970.

RANCIÈRE, Jacques, « L’histoire « des » femmes : entre subjectivation et représentation (note critique) », Annales. Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations, vol. 48, n°4, 1993, p. 1011-1018.

RANCIÈRE, Jacques, Le partage du sensible. Esthétique et politique, Paris, La Fabrique, 2000.

RIBIÈRE, Mireille, BAETENS Jan, Time, Narrative & the Fixed Image / Temps, narration & image fixe, Brill, 2001.

RICŒUR, Paul, Temps et récit, t. 1 : L’intrigue et le récit historique, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 1983.

SHOWALTER, Elaine, A Literature Of Their Own: British Women Novelists from Brontë to Lessing, Londres, Virago, 2009.

SCHAEFFER, Jean-Marie, Les troubles du récit. Pour une nouvelle approche des processus narratifs, Paris, Éditions Thierry Marchaisse, 2020.

ŠKLOVSKIJ, Viktor Borisovič, « Iskusstvo kak priem », in O teorii prozy, Moscou, Krug, 1925, p. 7‐23. / CHKLOVSKI, Victor, « L’Art comme procédé », in Tzvetan Todorov (dir.), Théorie de la littérature : textes des formalistes russes, trad. Tzvetan Todorov, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 1965, p. 75‐97.

TSENG Ching-Pin, « Narrative and the Substance of Architectural Spaces: The Design of Memorial Architecture as an Example », Ahens Journal of Architecture, vol. 1, n° 2, 2015.

TUMBAS, Jasmina, « I Am Jugoslovenka » : Feminist Performance Politics During and After Yugoslav Socialism, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2022.

VIALA, Alain, « Effets de champ et effets de prisme », Littérature, vol. 70, n°2, 1988, p. 64‐71.